TREATMENT OF AN US SOLDIER DEVELOPING HEMORRHAGIC FEVER WITH RENAL SYNDROME DURING THE 34TH KFOR MISSION IN KOSOVO

Hämorrhagisches Fieber mit renalem Syndrom – Behandlung eines amerikanischen Soldaten während des 34. KFOR-Einsatzes im Kosovo

Aus der Inneren Abteilung¹ und der Sektion Tropenmedizin am Bernhard-Nocht-Institut für Tropenmedizin⁴ (Abteilungsleiter: Oberstarzt Dr. C. Busch; Leiter Fachbereich Tropenmedizin: Oberfeldarzt Dr. H. Sudeck ) des Bundeswehrkrankenhauses Hamburg (Chefarzt: Generalarzt Dr. J. Hoitz), der Klinik für Innere Medizin² (kommissarischer Ärztlicher Direktor: Flottillenarzt Dr. M. Vogelpohl) am Bundeswehrkrankenhaus Ulm (Chefarzt: Generalarzt Dr. A. Kalinowski) und aus dem Department of Emergency Medicine, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, Texas, United States of America³ Nathan Borden, MD, CPT (03).

Nicole Müller¹, Enno Rother², Nathan Borden³, Hinrich Sudeck⁴

WMM, 58. Jahrgang (Ausgabe 6/2014, S. 206-209)

Summary

Soldiers in foreign missions are at principle risk of acquiring zoonotic diseases. We present a severe course of a Hantavirus infection in an U.S. Army infantryman during his KFOR deployment. He presented with a febrile gastroenteritis with signs of sepsis. Laboratory tests were remarkable for thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy.

Differential diagnosis comprised among others the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), which is endemic in Kosovo. MED-EVAC transportation to Germany was not possible until the CCHF was ruled out. In the course the patient developed oliguric renal failure, respiratory impairment and a posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. After extensive intensive care treatment the soldier recovered from his Hantavirus infection. This case illustrates the importance of deployed providers understanding theatre-specific medical threats including local zoonotic disease.

Keywords: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, Hantavirus infection, Dobrava, Kosovo

Zusammenfassung

Soldaten im Einsatz sind einem erhöhten Risiko zoonotischer Erkrankungen ausgesetzt. Wir stellen einen schweren Verlauf einer Hantavirusinfektion eines US-Soldaten während des KFOR-Einsatzes vor. Der Patient zeigte eine schwere fieberhafte Diarrhoe als Intialsymptomatik mit Zeichen der Sepsis. Laborchemisch fand sich eine ausgeprägte Thrombozytopenie und Koagulopathie. Unsere differentialdiagnostischen Überlegungen umfassten auch das Crim-Congo-Hämorrhagische Fieber, welches endemisch im Kosovo ist. Erst nach Ausschluss eines CCHF war eine MED-EVAC aus dem Einsatzland möglich. Im weiteren Verlauf entwickelte der Patient ein oligurisches Nierenversagen, eine respiratorische Insuffizienz und eine posteriore reversible Encephalopathie. Nach umfangreicher intensivmedizinscher Therapie erholte sich der Soldat ohne bleibende Folgeschäden.

Schlagworte: Hämorrhagisches Fieber mit renalem Syndrom, Hantavirus-Infektion, Dobrava, Kosovo

Clinical case

In May 2013 a 37-year old male soldier was transferred to our role-3-hospital in Camp Prizren, Kosovo, complaining of epigastric discomfort, emesis and severe nonbloody diarrhea with 20 bowel movements/24 h. His review of symptoms was remarkable for mild headache fatigue and paresthesia in both hands. Symptoms had started four days earlier after a physical fitness test, including nausea and vomiting, followed by the development of fever up to 39 °C, headache and diarrhea. He presented to the Camp Bondsteel Emergency Department (ED), Kosovo, for evaluation and treatment. In the ED he received symptomatic treatment for dehydration and given his fever, headache, and mild cognitive impairment meningitis was high on the differential. He received empiric Ceftriaxone and Vancomycin for meningitis. Laboratory evaluation of his cerebrospinal fluid was within normal limits. Despite intravenous fluid resuscitation and antibiotics the patient continued to deteriorate evidenced by his worsening diarrhea and decreasing platelet count. The decision was made to transfer the soldier to a higher level of care at Camp Prizren, Kosovo, where more advanced diagnostic and treatment modalities were available.

The patient, an active duty U.S. Army infantryman stationed at a remote base in northern Kosovo, denied any past medical or surgical history. He also denied ticks bites, eating on the local economy and other soldiers in his unit having similar symptoms. Beside the Balkan there was no significant travel history.

Upon admission the patient appeared alert, diaphoretic and lethargic. His initial vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, pulse 63/min, SpO2 on room air 92 %, temperature 38,7 °C, and respiratory rate 35/min. The skin and mucous membranes were dry without petechiae, rash or edema. There was no jaundice. His heart and lungs were clear to auscultation without wheezing, rales or rhonchi. The abdominal exam was remarkable for mild diffuse abdominal tenderness with increased, non-pitched bowel sounds, and no guarding, rebound or flank pain. The neurological exam was unremarkable except for lethargy. He had no nuchal rigidity. There was no joint swelling or tenderness. The initial laboratory work (see table 1) was remarkable for severe thrombocytopenia (13.000/µl), a prolonged aPTT (53 sec.) and an elevated LDH (433 U/l).

The abdominal ultrasound showed moderate splenomegaly (16x5cm), prominent small bowel loops with normal peristalsis. There was ascites and retroperitoneal free fluid. The CT scan revealed a moderate edema of the intestine, confirmed splenomegaly and showed massive intraperitoneal fluid collections. There were subtle pleural effusions bilaterally, but no pneumonia. His respiratory status prompted an evaluation of his acid-base status which revealed a combined disorder. There was a metabolic acidosis likely due to bicarbonate loss from diarrhea and a primary respiratory alkalosis, presumably from sepsis-induced hyperventilation. An echocardiogram showed cardiac involvement with developing clinical signs of hypotension and sinus bradycardia of 30bpm. The patient’s clinical, radiographic and laboratory evaluations were consistent with severe sepsis likely from fulminant gastroenteritis. He was therefore treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics including Piperacillin/Tazobactam and Ciprofloxacin accompanied by fluid replacement. Due to the splenomegaly, elevated LDH and relatively low CRP level we also considered a viral (co-) infection or a hematological disease. Additional laboratory tests for a variety of respiratory and gastroenterological pathogens (e.g. Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Norovirus, Rotavirus, Adenovirus, Cl. diff.) were all negative. The peripheral blood smear showed thrombocytopenia, some megathrombocytes, immature granulocytes and no fragmented red blood cells or atypical white blood cells, making a hematological disease unlikely.

We also considered Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), which is endemic in Kosovo, as a differential diagnosis. However, the patient’s lack of bleeding and hepatic involvement were inconsistent with CCHF at this stage. Nevertheless we decided to establish strict hygienic protections for the staff and ordered serological testing, which was not available at our facility. The analysis was provided by the civilian University Hospital Center in Prishtina, Republic of Kosovo. In addition to CCHF we considered Hanta virus infection. The patient’s austere living conditions at remote military installations places him at risk for exposure to Hanta virus vectors. Clinically, the patient’s nephritic urine is concerning for possible Hanta infection. His urea and creatinine levels were normal at admission, but went into non-oliguric renal failure within the following days.

Despite our therapeutic measures the overall status of the patient further deteriorated. The lethargy did not improve and a follow-up echocardiography showed worsening global left ventricular function consistent with septic cardiomyopathy. A CT scan of the head was done to rule out intracerebral bleeding as a cause of headache and lethargy. At that time the patient also reported visual disturbances which resolved spontaneously. Due to limitations of our facility concerning transfusion of platelets and hemofiltration we requested an urgent MED-EVAC transportation to Germany (Landstuhl Regional Medical Center - LRMC) on the following day. Since patients with even the slightest suspicion of hemorrhagic fever do not get entry permit for countries of the European Union, medical evacuation had to be delayed until the CCHF testing was completed.

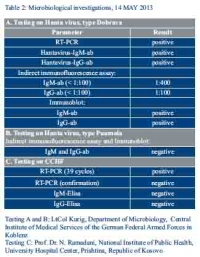

The serological analysis showed a positive result for Dobrava virus, a strain of Hantavirus (see table 2). Surprisingly, the first testing for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever also showed a delayed positivity after 39 cycles of PCR testing. Because of further clinical deterioration and this debatable result of CCHF-PCR we initiated an antiviral treatment with ribavirin in standard dose of 16 mg/kg body weight every 6 hours, administered under ICU conditions. However, confirmatory PCR and ELISA on CCHF presented a negative result. Thus in excellent collaboration with the US Army we finally were able to MED-EVAC our patient to Germany, Lanndstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC).

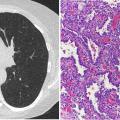

At the LRMC the patient presented progressive non-oliguric renal failure with a peak creatinine of 4.8 mg/dl plus respiratory failure requiring intermittent bipap-ventilation. Platelets were given to prevent bleeding and thereafter remained stable. Entering the polyuric phase of illness on day 4 after admission to the LRMC the patient started to improve, when on day 6 unexpectedly presented two seizures, revealing changes on MRI consistent with a posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). On tight blood pressure control and anti-seizure medication the patient finally improved. Follow up MRI showed improvement, creatinine levels returned to baseline of 1,1 mg/dl without necessity of hemofiltration. The patient has meanwhile returned to his home country recovering from this atypical Hantavirus infection.

Discussion

Hantavirus Infections causing different forms of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) can be associated with a relevant morbidity and mortality. Immediate evaluation and correct treatment are important to prevent a fatal clinical course. Infection is mainly acquired by inhalation of aerosolized virus or contact with urine or feces of infected rodents. The rodent host on the Balkans is the yellow-necked field mouse – Apodemus flavicollis (picture 1). Even transmission from person to person has been reported [1].

Throughout Europe and the Balkans prevalent strains of Hantavirus are Puumala (PUUV), Dobrava (DOBV), and Saaremaa spp. (SAAV), which are known to cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome [2]. PUUV causes a generally mild form of the disease, the so called nephropathia epidemica, whereas the subtype DOBV more often presents with hemorrhagic complications due to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia [1, 2]. The DOBV infection usually starts abruptly with fever, headache and gastrointestinal symptoms [3] followed by renal failure, sometimes visual disturbances and thrombocytopenia. Although gastrointestinal symptoms are common, extensive diarrhea like in our patient has not been described in the literature. Pleural and abdominal effusions as well as cardiac disorders are encountered frequently [3, 4, 5, 6]. Overall mortality rates range from 5 - 15 %. The clue to the diagnosis of Hantavirus in our case was thrombocytopenia and a nephritic urine sediment plus a possible exposure to rodents, though renal failure was still missing by the time of admission. Relevant thrombocytopenia occurs in the majority of patients and thrombocyte levels below 50.000/µl develop in more than half of the cases, but the extent of decrease in platelet count as in our case (lowest platelet count 9.000/µl) has not been described so far [7]. Peripheral blood smear revealed immature granulocytes and macroplatelets which are supposed to be seen frequently in Hantavirus infections [7]. Sepsis-like presentations of severe Hanta-Virus are common [8].

Laboratory findings suggestive of the diagnosis Hantavirus infection include leucocytosis, a rapid decline in platelet count, an elevated LDH and renal involvement, which includes proteinuria, hematuria and reduced glomerular filtration rate. Other possible abnormalities include an increase in serum levels of lactate and an elevation of liver enzymes. The latter was missing in our patient. In acute infection, viral RNA is detectable from serum by PCR, later the diagnosis of Hantavirus infection is based on serology. Even in the so called prodromal phase of the disease IgM- and usually also IgG-antibodies are present. Besides positive testing on Hanta virus, we also got a positive result in CCHF-PCR in the first place. Confirmation testing for CCHF was done and consistent to our clinical impression turned out to be negative. Possible laboratory contamination has to be discussed since the Laboratory in Prishtina had dealt with two other confirmed cases of CCHF at the same time.

There is no specific antiviral therapy for hantavirus-infection. Therefore treatment is mainly symptomatic. Although one prospective double-blinded study in patients with proven Hantavirus infection found that administration of intravenous ribavirin led to a reduction in mortality, the efficacy of this drug is still discussed [9, 10, 12]. Few cases have been reported with persistent chronic renal failure after infection with Dobrava virus. Steroids seem to be an option for these patients [11].

Conclusions

Rodent-borne infections like Hantavirus can present as a severe, sepsis-like disease with hemorrhagic fever and a potentially lethal outcome. Soldiers are at particular risk for sporadic or endemic outbreaks. In Kosovo CCHF is an important differential diagnosis of hemorrhagic fever. Availability of rapid and high-quality diagnostic testing for these diseases is essential to confirm or rule out a specific infection. Otherwise life-saving MED-EVAC can be delayed with potential harm to the patient.

Bildquelle: Abb. 1: James Lindesy at Ecology of Commanster, http://www.commanster.eu/commanster/Vertebrates/Mammals/SpMammals/Apodemus.flavicollis.html (Accesed 21 Feb 2014)

Literature

- Vapalahti O, Mustonen J, Lundkvist A, et al.: Hantavirus infections in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 2003; 3: 653-661.

- Markotić A, Nichol ST, Kuzman I, et al.; Characteristics of Puumala and Dobrava infections in Croatia. J Med Virol 2002; 66: 542-551.

- Rollin PE, Coudrier D, Sureau P: Hantavirus epidemic in Europe 1993. Lancet 1994; 343: 115-116.

- Rasmuson J., Lindqvist P., Sörensen K., et al.: Cardiopulmonary involvement in Puumala hantavirus infection. BMC Infect Dis 2013 Oct 28; 13(1):501 (Epub ahead of print).

- Makela S, Kokkonen L, Ala-Houhala I, et al.: More than half of the patients with acute Puumala hantavirus infection have abnormal cardiac findings. Scand J Infect Dis 2009; 41: 57.

- Puljiz I, Kuzman I, Markotić A, et al.: Electrocardiographic changes in patients with haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Scand J Infect Dis 2005; 37: 594.

- Kuzman I. Clinical picture of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Croatia. Acta Med Croatia 2003; 57(5): 393-397.

- Steinberg BE, Goldenberg NM, Lee WL: Do viral infections mimic bacterial sepsis? Antiviral Research, 2012; 93, 2-15:

- Huggins JW, Hsiang CM, Cosgriff TM, et al.: Prospective, double-blind, concurrent, placebo-controlled clinical trial of intravenous ribavirin therapy of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. J Infect Dis 1991; 164: 1119-1127.

- Ogg M, Jonsson CB, Camp JV, et al.: Ribavirin protects syrian hamsters against lethal hantavirus pulmonary syndrome – after intranasal exposure to Andes virus. Viruses 2013; 5(11): 2704-2720.

- Martinus Bergoc M Lindic J, Kovac D, Ferluga D, et al.: Successful treatment of severe hantavirus nephritis with corticosteroids. Ther Apher Dial. 2013 Aug; 17(4), 402-06.

- Rusnak JM, Byrne WR, Chung KN et al.: Experience with intravenous ribavirin in the treatment of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Korea. Antiviral Research 2009; 81(1): 68-76.

Datum: 18.07.2014

Quelle: Wehrmedizinische Monatsschrift 2014/6